Commeraw Stoneware at the Halsey House: Old artifacts tell new stories

- Sarah Kautz

- Feb 28

- 4 min read

Why are the artifacts in the Southampton History Museum's collections important? Like other history museums, our collections serve as a repository of materials that represent tangible evidence of our past. The objects preserved in our collections allow people to explore the past through new research and new questions–all contributing to more nuanced understandings of history and culture. Likewise, as new information about the past is uncovered, the stories we tell through our collection become richer and more dynamic.

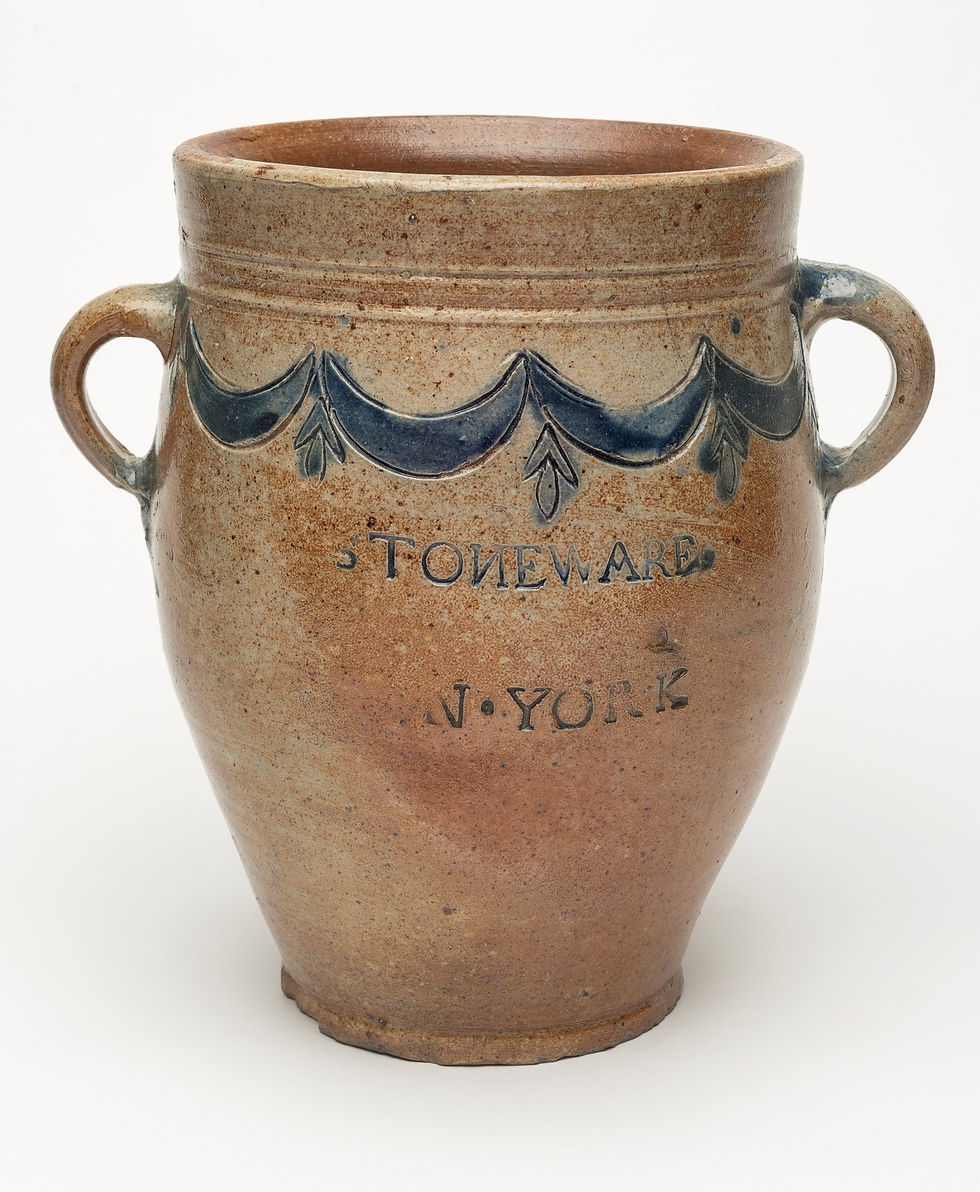

For example, consider the two pieces of stoneware pictured here that were excavated at the Southampton History Museum’s Thomas Halsey House (settled 1648, built ca. 1683). The excavations at Halsey House took place during the 1980s and 1990s and were organized by Richard Spooner (1922–2015). A native of Floral Park, NY, he assisted at archaeological digs in Queens under the direction of professional archaeologists including Ralph Solecki (1917–2019) before coming to Southampton in 1956. Spooner was a former principal of Southampton High School and served as the Mayor of Southampton Village from 1989 to 1993.

Although the fragments were unearthed decades ago, nothing specific was known about who produced this stoneware or where it was made. Our understanding of these fragments dramatically changed a few years ago thanks to new research by Jean Held (1936–2023), who identified their maker as Thomas W. Commeraw (active ca. 1796–1819), a free African American master potter and entrepreneur who operated a business in Lower Manhattan.

The fragments from Halsey House came to Held’s attention during her research for an exhibition at the Sag Harbor Historical Society in 2021 entitled, Beachcombing for Artifacts of Sag Harbor History. The exhibition featured artifacts recovered by Held from nearly 10,000 cubic yards of dredged sediment from Sag Harbor’s Long Wharf deposited at Havens Beach during a construction project between 2017 and 2019. Held’s finds included at least three fragments of Commeraw pottery, pictured below. Luckily the dredged artifacts were saved by Held and others, whose care and concern helped mitigate the irreversible loss of important archaeological evidence about Sag Harbor’s role as a historic port of commerce.

The fragments of Commeraw pottery along with other objects from Long Wharf reflect the variety of goods that were once shipped through Sag Harbor, connecting eastern Long Island with national and global maritime trade networks. A similar variety of artifacts were found during archaeological investigations conducted in 2004 and 2005 at Battery Park in Lower Manhattan. As part of investigations to mitigate disturbance by improvements to South Ferry Terminal, archaeologists located the remains of Whitehall Slip, where ships carrying goods docked in colonial and early American periods.

During the years when Commeraw was actively making stoneware (ca. late 1790s–1819) at Corlear’s Hook, just a short distance up the East River from Whitehall Slip, Sag Harbor was an official port of entry for the United States. The artifacts from Long Wharf and Halsey House indicate that some of the thousands of utilitarian stoneware vessels made by Commeraw were shipped to eastern Long Island. The busy port at Sag Harbor connected Southampton and other communities on eastern Long Island with wider trade networks, providing access to goods that were more commonly found at wealthier port cities like New York City and Boston.

New research not only yields more information about the past, but helps us to more fully understand and recognize the contributions of people who might otherwise be overlooked. Commeraw himself was not recognized as a master craftsman of color until 2010. Yet, his distinctive stoneware jars and jugs, decorated with his signature Neoclassical swags and tassels and stamped boldly with his name and location, were familiar to collectors and curators for well over a century. His pots were collected and interpreted under the erroneous assumption that Commeraw was a white potter of European descent. However, in 2010, new research by scholar Brandt Zipp revealed Commeraw’s African American identity. Zipp’s research not only allowed us to fully recognize Commeraw’s excellence as craftsman of color, but also his legacy as an entrepreneur, abolitionist, and leader in New York City’s early American free Black community. Commeraw’s newly acknowledged identity and contributions to American history were celebrated at the New-York Historical Society’s 2023 exhibition, Crafting Freedom, the first single-artist show dedicated to his life and work. As Margi Hofer, former curator and museum director of the New-York Historical Society noted, “I hope the story of Commeraw’s identity is a cautionary tale to not make assumptions about identity when we look at objects from the past.”

The Southampton History Museum is grateful for the intellectual curiosity of past, present, and future researchers like Richard Spooner, Jean Held, and Brandt Zipp. Thanks to their dedication to learning and investigation, we can now share the remarkable story of Thomas W. Commeraw through two pieces of pottery unearthed in Southampton at the Halsey House.

Want to learn more about Commeraw? Watch this video by the New-York Historical Society:

.png)