High Style in the Gilded Age: Frances Breese Miller

- Mary Cummings

- Mar 2, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 26, 2022

FRANCES (TANTY) BREESE MILLER 1893-1985

Frances Breese Miller lives a life in two acts. In the first, she is born into the mannered elegance of 19th-century wealth and privilege as the daughter of James Lawrence Breese and Frances Tileston Potter Breese. In the second, she will turn her back on its conventions to become a liberated woman of the 20th century. In her later years, in a three-volume memoir self-published between 1979 and 1981, she will record her passage from sheltered child and Junior League debutante to the artist and committed environmentalist she became.

Hers is a fairy-tale childhood, but with a twist. It is obvious almost from the beginning that Tanty, as she is nicknamed, is her father’s daughter, a tomboy whose resistance to ladylike behavior he applauds. James Breese has a well-earned reputation as a bon vivant, his interests revolving around photography, automobiles and all things beautiful, including women. His best friend is Stanford White and, like the celebrated architect who is a partner in McKim, Mead and White, Breese enjoys the benefits conferred by his high rank in society as long as they do not interfere with his free-spirited pleasures. With his approval, Tanty adopts a similar attitude, never an openly rebellious child but finding pleasure nevertheless in activities deemed too robust for a young girl in Gilded Age society.

In 1880, James Breese had taken the conventional path in his marriage to Frances Potter, the product of a strict religious upbringing--an exceptionally poor match for a sensual man with bohemian tastes. Her own mother had died in childbirth, leaving little Fanny to be raised in a large two-bishop family. Her uncle Alonzo is the Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania and her uncle, Henry Codman Potter, the very influential seventh Bishop of New York.

Steeped in piety at home, Fanny is immersed in Victorian propriety at the English boarding school to which she is consigned at the age of eight. Tanty describes her mother as a noble woman, beautiful in the “grande dame” style, a good amateur pianist, skillful horsewoman and driver, gifted in flower arranging but lacking in warmth. Inevitably, the marriage of opposites is not a happy one, and Fanny suffers frequent emotional breakdowns. Conditioned to be inhibited, she is the outsider in a household comprised of an uninhibited husband, three boisterous sons and a tomboy daughter.

One of Tanty’s early childhood memories is of accompanying her mother on a visit to “Box Hill,” the Stanford Whites’ country home in St. James. Fanny Breese and Bessie White are close friends, comrades-in-arms in the struggles associated with wayward husbands. Tanty has her own reasons for enjoying the visits. She is charmed by Bessie’s warmth and vitality, but mostly she is fascinated by Bessie’s remarkable ability to whistle and sing a tune at the same time.

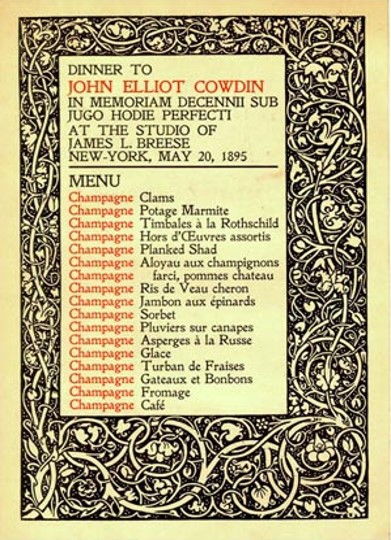

Invitation to a Stagfest

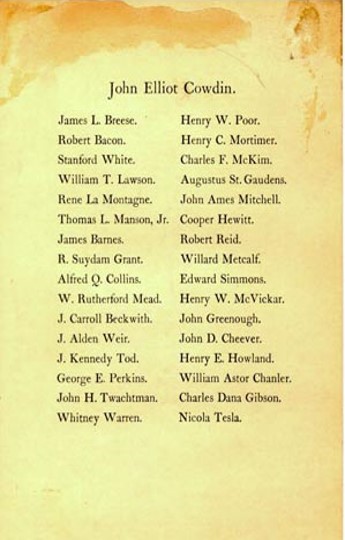

With husbands who have never accepted that marriage might require putting a stop to their bachelor carousing, Fanny and Bessie share a certain fortitude in facing their common fate. In 1895, it is put to the test when White and Breese host a supposedly secret stag party that is somehow leaked to the press. Under pretext of a celebration honoring John Elliot Cowdin, a silk factory titan, the gathering at Breese’s elaborate photography studio is attended by some 50 men, among them Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Charles Dana Gibson and Nicola Tesla.

Rabelaisian quantities of food and drink are consumed, climaxed by dessert in the form of a huge six-foot pastry out of which pops a flock of birds and a scantily clad underage girl. The press makes hay with this image of the affair, to be known ever after as the “Pie Girl Dinner.” And despite Charles Dana Gibson’s protestations that the event was “very moral and dignified,” it is blasted in the NY World as a particularly outrageous example of the fashionable crowd’s “bacchanalian revels.” Participants may be embarrassed by the public rebuke but the sting of humiliation is surely most deeply felt by their wives.

A committed New Yorker, James Breese spends most of his time in the townhouse on 16th Street, which serves as not only as his photography studio--known as the Carbon Studio—but also as living quarters and a gathering place for his bohemian friends.

But the patriarch chooses to tuck Tanty and the rest of the family away in staid Tuxedo Park. In 1887, with his finances--always in flux with the market--on the ascent, he is able to hire architect Robert H. Robertson--the Southampton summer resident who designed the Rogers Memorial Library, among much else--to build “The Breezes,” the family’s massive Tudor Revival residence in Tuxedo.

Never quite suited to decorum-obsessed Tuxedo society, Breese finds it expedient to make his exit from the elite country refuge in the Ramapo Hills when Tanty is just two. The offense that probably precipitates his departure is his promotion of a craze for tobogganing down the club’s stairs on silver tea trays. When some younger enthusiasts expose the lacy underpinnings beneath their skirts on the way down, outraged dowagers put an end to the fun, and to the Breese family’s residency in the stodgy WASP paradise.

Happily, times are good and not long after his retreat from Tuxedo, Breese purchases about 30 acres on Hill Street in Southampton and begins the long process of folding an original modest structure into the magnificent country estate he calls The Orchard. His friend Stanford White is generally credited with the sumptuous interior design, while his partner Charles McKim takes the honors for the exterior. Both work closely with James Breese, who once entertained thoughts of becoming an architect himself.

Tanty is five in 1898 when the Breeses finally move in for the summer, though Tanty later recalls that the family took meals at the popular Irving House across the street while The Orchard received its final touches.

Summers at The Orchard are carefree with 30 acres to roam and an indulgent father who encourages Tanty’s adventurous spirit. Back in the city when summer is over, she receives instruction from her governess and becomes more fluent in French than in English, speaking it with a French accent, much to the amusement of her older brothers. Not until she is 10 years old is she sent to school, a move toward independence which delights her, though at home she’s still expected to perfect the ladylike skills of sewing and drawing. She complains that they are taught so unimaginatively that she would much prefer to be creating stylish clothes for her paper dolls, reading a book or, ideally, joining her brothers in their far more interesting activities. They, of course, want no part of her.

When Tanty is about 12 years old, James Breese’s fortune, which rises and falls with the vagaries of the market, plummets in value necessitating the sale of his 16th Street townhouse, the temporary abandonment of The Orchard to tenants, and a stint as a farmer in Maryland. Her “adaptable father,” greets the rustic experiment with his usual gusto. He purchases a run-down farm, dons overalls and learns to drive a tractor. For Tanty, it as a lonely time. With no money for boarding school, she is sent to a private day school in Baltimore, an intolerably arduous, time-consuming commute that allows no time for making friends, and then to an all-boys school, where she feels her outsider status even more acutely. Permission to drive a car alone on the back roads is one bright spot. Her dogs, her only companions, are another. But by the time she is 16, her father has recouped some of his losses and she is overjoyed to learn that she will be sent off to boarding school in the fall - in Paris!

With the end of the Maryland experiment, Tanty is heading into much more exciting times. In her memoir she describes a thrilling experience that summer, which seems to signal the change. “A memorable occasion for me,” she writes, “was the day in my fifteenth year that my father and I had set out from New York for eastern Long Island in our six-cylinder Pierce Arrow.” Once they cross the Queensborough Bridge, she is allowed to take the wheel, a big surprise since up to that time she has only driven in the country. “I was filled with pride,” she writes “when my father opened his newspaper to look at the stock market reports instead of watching my driving. He then let me drive the entire one hundred miles to Southampton.”

At The Orchard, the Pierce Arrow shares garage space with a Mercedes, a Crane Simplex and an electric brougham, which is no longer useful in the city. Emboldened by her demonstrated driving skills, Tanty convinces her father to turn the electric vehicle--which has a maximum speed of 15 mph--over to her. The only female driver in town, she is the envy of her friends as she arrives each day at the Meadow Club for tennis and then on to the beach. Boarding schools in first Paris, Then Florence.

That winter is spent in Paris where the tomboy is exposed to the cosmopolitan graces so important to her mother. The following winter she attends a boarding school in Florence to put the finishing touches on her preparations for a life in society. She speaks several languages, is well traveled and will never disgrace herself in a drawing room but she remains her father’s daughter. Back home, at 18, she uses her savings and, with some help from her father, acquires a four-cylinder Hupmobile of her own.

With money again tight, there will be no elaborate coming-out party for Tanty, but her friends entertain lavishly and her social calendar is full during winters in New York and summers in Southampton. She calls this time, as a single and popular member of the young smart set, her “dancing days.” She is, in fact, a talented dancer and when she and one of her glamorous debutante friends are asked to appear in a charity benefit performing a snake dance, they approach the celebrated modern dancer Ruth St. Denis for advice on their costumes. Reptile sins are purchased, arms painted green, and the two are a hit with their graceful contortions.

It’s not all parties and dancing. In 1912, Tanty is elected chairman of the Junior League and her work for the organization opens her eyes t a different New York City. She takes the elevated train to a settlement house on Hester Street to teach ballroom dancing to a group of Italian girls—waltzes, fox trots and two steps. No snake dancing. In midtown, she visits foster homes for the Children’s Aid Society and is shocked by mothers who threaten their children with the strap one minute and embrace them the next. She gets to know some of the social workers and is filled with admiration for the dedication of these college-bred, self-supporting women.

And then, at the end of her second winter in New York, Tanty does exactly what is expected of her. She becomes engaged to the charming young Lawrence McKeever Miller, whose parent had been neighbors in Tuxedo Park and whose grandparents, the McKeevers, were well known summer residents of Southampton even before the Breeses arrived. Though Tanty’s mother had hoped for a richer, more prestigious husband for her only daughter, her father welcomes Larry to the family, pleased that he will be able to discuss the market with a fellow Wall Streeter. The courtship marks the first time Tanty is ever allowed to go out with a man unchaperoned. When the engagement is announced in the spring of 1915, the society press is ecstatic and James Breese starts making elaborate plans to decorate the magnificent Music Room at the Orchard as a suitably spectacular setting for a Breese wedding.

On October 9, 1915—the same day that her brother Robert and Beatrice Claflin are married at St. Andrew’s Dune Church—Tanty, on the arm of her father walks down the aisle he has created by stringing white ribbon down the center of the 70-foot room. At the end is the antique Italian altar where her father—resplendent in cutaway coat and striped trousers—delivers her to her betrothed.

Tanty wears a long white satin gown and a rosepoint court train made of lace said to have belonged to the empress Eugenie of France. After the service, attended by some 100 friends and family, Robert and Beatrice Breese arrive from St. Andrew’s with their entourage for a double reception at The Orchard. George Morris of Southampton’s Morris Studio is on hand to photograph the marvelous event which gets breathless coverage in the New York press. When the bride and groom are ready to leave for their honeymoon, they are driven to the depot where a one-car private train sweeps them away. To smooth their path, Mayor Elmer Smith had ordered all traffic on Jobs Lane and Main Street stopped to allow their car to speed through.

There are happy times in the early days of the marriage. Tanty soon gives birth to a daughter they name Edith and later there will be twin sons. But differing outlooks soon emerge as Tanty’s independent nature and creative spirit make her husband uncomfortable and cause problems. Then, with U.S. entry into World War I on the horizon, things change. Tanty learns to drill and carry a rifle at the Armory and is a Red Cross volunteer. When Larry is eventually drafted and sent to camp Upton, coping alone is difficult but undeniably liberating. With Larry serving in France, Tanty rents a house on Herrick Road, continues as a Red Cross volunteer and learns typing and automobile repair. When Larry returns after a year’s absence, it is to a different woman.

In Hewlett, where the Millers reside after the war, suburban life frustrates Tanty. She looks forward to summers in Southampton and when her father remarries and brings his bride—a young woman roughly Tanty’s age—to The Orchard, she and Larry rent a house of their own. When the well-known artist Rachel Hartley, who has a studio in Hampton Park, admires some of Tanty’s casual work and encouraged her to paint seriously, she is thrilled. But Larry disapproves and she gives up painting. It’s a sign of worsening tensions to come when, tormented by indecision concerning the future of her marriage, Tanty has a nervous breakdown, After 14 years, she and Larry agree to separate and in 1930 Tanty travels to Reno to get a divorce.

Even before the divorce, Tanty had stretched her wings by accepting a partnership in a small New York shop called Books and Things, a departure from her domestic duties which, to her surprise, Larry—a practical man—made no objection. When the things in the shop, which reflect Tanty’s eye for modern design, eventually overwhelm the books, it’s a first step toward what will lead to her successful career as an avant garde textile designer. After the divorce, newly independent and with a growing business, Tanty—always drawn to Southampton and the sea—acts on her desire to have her own house there and to give her children the experience of a simpler life apart from the rituals of Southampton’s fashionable society. In 1933, she buys a piece of oceanfront land in Bridgehampton, paying $75 a front foot. Not long after that, when she learns that the land next door is owned by the Riverhead Library, which is not interested in keeping it, she pays $45 a square foot for it and begins sketching designs for “The Sandbox.”

With a flat roof and rectangular lines, the Sandbox is inspired by the modernist architecture Tanty had seen in Europe and realized with the help of architect Lansing Miller. It is unpretentious and playful, meant for carefree summer living. Equally important to Tanty, it makes a small imprint on the beach environment but a big hit with her children and the many friends she entertains there. Professionally, her reputation continues to grow. She is winning awards and commissions, and in 1939 she is asked to design the carpet for the United States Building at the Chicago World’s Fair.

Tanty lives the rest of her life as a truly liberated woman, no longer a part of the privileged and cloistered New York-Southampton society she was born into. Her career thrives in the thirties and forties and she remains creative and adventurous for the rest of her long life. A decision to live for a time in Haiti has significant consequences in the post-World War II years. Her painting and other creative work shows the influence of her surroundings but, more significantly, she falls in love with a Haitian. It is a happy time in Haiti but when they marry and settle in the States, there are problems. Tanty’s friends admire her unconventionality in marrying a black man but others do not, adding to the tension felt by her husband in an unfamiliar country with an unfamiliar language. Despite a move to Mexico, the marriage ends in divorce.

With the return of her husband to Haiti, Tanty resumes life in Mexico until 1957 when she returns to The Sandbox, the place she realizes she loves most of all. In her ninth decade she is sometimes in New York, sometimes in Florida, sometimes in Sag Harbor for the winter, but when summer comes, she heads for The Sandbox and sets up her easel. In June 1985, at the age of 91, her very full life comes to an end.

.png)