GRACE CLARKE NEWTON - The Poet

There is mystery and romance in Grace Clarke Newton’s story, though as the daughter of the noted collector, close friend of Stanford White, and popular man-about-town Thomas B. Clarke, her path to a good marriage and a privileged life in New York society seems foreordained. When the Clarkes move into the elegant Georgian townhouse with its medieval bow windows--a Stanford White design--their residence at 22 East 35th Street is duly noted in the Social Register, along with Thomas Clarke’s memberships in all the right clubs. As one of Clarke’s four beloved daughters and sole son, Grace seems headed for a life without drama.

Grace’s mother, the former Fanny Eugenia Morris, hails from a distinguished family and her marriage to Thomas Benedict Clarke in 1871 is no doubt applauded by family and friends. Clarke combines an astute business sense with an artistic sensibility and moves easily in New York society. Having started out as a manufacturer of laces and linens, he moves on to become a dealer in Chinese porcelain--J.P. Morgan’s porcelain advisor--and then to rise in the art world as the country’s foremost collector of contemporary American art.

In the small world of New York City aesthetes--artists, men-of-letters and wealthy bohemians--Clarke and the celebrated architect Stanford White are destined to become close friends. White is among the high-living circle of artists and wealthy patrons who come and go at 22 East 35th Street, enjoying the Clarkes’ hospitality in the elegant home White designed for his friend Tommy at no charge.

Parlor – Townhouse of Thomas B. Clarke

Master Bedroom – Townhouse of Thomas B. Clarke

In a letter to White expressing their delight in their exquisite townhouse, the Clarkes write: “Your genius and taste is everywhere shown in [our] beautiful house…”

The walls are surely hung with selections from Thomas Clarke’s unrivaled collection of paintings by American artists, which, as early as 1878, included such giants as George Inness, Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Church and William Merritt Chase. By then, Clarke had already amassed 185 paintings, among which 170 were by American artists.

Grace is no longer a child when the family moves into the highly distinctive townhouse, but there has never been a time when she has not been surrounded by art and artists. She seems to have been relatively free of parental pressure to hone the skills of a good wife and socialite, and encouraged to pursue her talent for writing stories and poetry. Much later, some of the many stories written in those early years are discovered and collected under the heading “A Small Girl’s Stories.” A note accompanying the collection identifies them as having been written when she was “a small girl of 11 years of age.”

Thomas Clarke is apparently a fond father and husband but, like many men of his class, he is known to straddle the line between the world of New York smart society and that of the bohemian artists, whose parties and amorous adventures are likely known, though not acknowledged by others, including their wives. In the Gilded Age, it’s generally accepted that privileged men will gather together for revels that exclude the inhibiting presence of their wives. In this illustration the carousing at a stag banquet for one of their number is well underway. The bald Thomas Clarke can be seen seated facing the camera next to the bearded Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

Elsie Ferguson

When Stanford White holds a luncheon for four at the start of his infamous affair with the showgirl Evelyn Nesbit, Thomas Clarke arrives with another showgirl, Elsie Ferguson. To Nesbit, then 16, Clarke looked “as old as Methuselah” but she notices how very attentive he is to Elsie. Later, when White is forced to give up the lease on the elaborate hideaway where the luncheon takes place, Clarke agrees to share the rental of a more modest space for clandestine meetings. Grace is no doubt in the dark about her father’s double life and indeed her own behavior seems to align effortlessly with what is expected of her.

Until it doesn’t. In 1900, Grace does something that shocks society, upends her family’s plans for her, and suggests a passionate and perhaps impulsive nature. According to press reports preserved in the Archives of the Social Register, Grace, a guest on a cruise aboard a yacht owned by Edwin Gould, son of robber baron Jay Gould, catches the eye of one Harry Wakefield Bates, who is immediately smitten. A socially prominent Bostonian, Bates is also an athlete of renown, having had a sensational career pitching for the Harvard baseball team.

After college, Bates buys into the once widely circulated Godey’s magazine with hopes of reversing its shrinking readership. But the magazine continues to lose ground and when it ceases publication in 1896, Bates moves on to a variety of more profitable enterprises.

Alerted to high romance on the high seas, the newspapers report that Bates has fallen “madly in love” with Miss Clarke, that he “urges his suit with ardor,” and soon has “Miss Clarke’s promise to be his wife.” He and Grace are secretly married in New York at the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin on June 19, 1900, the only witness being a friend of Mr. Bates.

Immediately after the ceremony Grace’s parents are notified by telephone and, taken completely by surprise, they leave The Lanterns, their East Hampton country home, for the city. Hints of “a stormy scene” appear in the society press but the next day Grace’s parents host a wedding breakfast at the very fashionable Delmonico’s on Fifth Avenue, “making the best of matters,” as the Boston Globe reports. Then the newlyweds leave for a wedding trip along the coast of Massachusetts and beyond on the groom’s yacht, the Gleam.

All appears well on their return until late August, when something happens between Grace and the love-struck Mr. Bates that abruptly breaks up the marriage. Only much later will some light be shed on the reasons for Grace’s sudden retreat--alone--to The Lanterns in East Hampton. Rumors that she will seek an annulment are followed by reports that she has been “taken ill with what appears to be nervous prostration.” A Social Directory advisory notes that letters to Grace are to be sent to the Metropolitan Club, care of her parents, suggesting that she may be convalescing in a treatment center and that there has been a parental intervention. (It is interesting to note that press coverage of the titillating affair invariably opens by identifying Grace as the daughter of “Mr. Thomas B. Clarke, the well known art collector,” Apart from her father, she seems to have no identity of her own in the eyes of the press.)

Recovery is apparently slow, as is the passage through legal channels of the case for ending the marriage. A suit filed in October 1900 comes before the fat and ponderous Judge James Fitzgerald in April 1901 (Five years later, Fitzgerald will preside over a much more sensational trial when Thomas Clarke’s good friend Stanford White is murdered by Evelyn Nesbit’s jealous husband). In the Bates divorce case, press reports are so discreet that Grace’s complaint remains a mystery. Claims that Bates had been married before and divorced are made and denied by Bates’s lawyer. Testimony from doctors, apparently at the crux of the matter, is deemed inadmissible. Letters, affidavits and all documents presented as evidence are read only by the judge. The public, avid for an explanation, has to be satisfied with Grace’s claim that Bates “had no right to marry her.” The trial ends with more confusion as Judge Fitzgerald denies Grace’s motion for the annulment and a headline in the New York Sun declares “Bates a Husband Still.”

At some point, Grace is returned to health and ready to put her romantic debacle behind her. But she’s not heard the last of the man she would most like to forget. In 1904 Maybelle Courtney, identified in the press as “a stage beauty,” makes headlines when she sues Harry Bates for $10,000 alleging breach of his 1902 promise to marry her. Bates makes the laughable claim that he was still married in 1902 and so couldn’t possibly have made such a promise. He is, in fact, reported to have filed for divorce from Grace in October 1903 on grounds of desertion, while Maybelle claims she was never told he was married. When he fails to set a date, Maybelle runs out of patience and Bates finds himself prosecuting a divorce libel at the same time he is defending an action for breach of promise. The press loves the story--a gift that never stops giving...until a Harvard bulletin reports that “after a lingering illness, “Harry Wakefield Bates died on December 12, 1904,” thus putting an end to his tangled romantic affairs, pulling the plug on Maybelle’s suit, and setting Grace free.

With her health restored, Grace goes on to recover her equilibrium, happy again in the Clarkes’ cheerful East Hampton home, decorated with ship’s lanterns from around the world. The Clarkes are enthusiastic members of the so-called “horsey set” out in the country. They join other fashionable spectators at polo matches, at fancy horse shows where polished equestrians compete, and cheer on the foxhunters who thrill to the chase. The Lanterns is known as a convivial gathering place for hunt breakfasts and in this lively society, Grace is courted by a prince of equestrian royalty: the tall, handsome master of hounds and renowned artist of hunting scenes and horses, Richard Newton, Jr.

Works by Amanda Brewster Sewell

The Newtons boast a long history on eastern Long Island. Richard’s father, the Reverend R. Heber Newton, who built a summer cottage on the dunes near Georgica Pond in 1888, was a superstar clergyman in New York until charges of “entertaining liberal religious views” led to his resignation in 1902. Young Richard Newton’s summers are spent at the beachfront cottage, acquiring the equestrian skills that are expected of a young man of his class, and benefiting as an aspiring painter from exposure to East Hampton’s artists’ colony. Among his neighbors in East Hampton are Robert and Amanda Sewell, determinedly bohemian artists who like to shake up the neighborhood with their plein-air painting sessions using nude models. After the Sewells take off for Morocco, Richard and his brother Francis spend several months in 1893 as their houseguests in Tangier.

That same year, as a 21-year-old with some private means, Richard purchases a house in Hayground and becomes a leading member of the local hunt club. In 1902, he establishes the Suffolk Hunt Club, eventually leasing the house to the club. World War I puts a temporary stop to the club’s activities. Then, after the war it is revived but relocates. Throughout the club’s existence Richard Newton serves as its master of foxhounds.

When Richard’s brother Francis purchases Fulling Mill Farm in East Hampton, the brothers are recognized as leaders not just of the hunt but of hunt society. In addition to the elaborate hunt breakfasts, there are race meets and other festive occasions that attract fashionable spectators dressed to the nines. Yet, for elegance, it ‘s hard to outshine the riders in full regalia. British tradition dictates black boots with brown tops, white breeches, canary yellow vests and scarlet coats for those talented enough to have earned the right to wear them. And while Richard is at the top of his game as a sportsman, he is also making a name for himself as a remarkably gifted equestrian artist.

Tall, sporty, yet natty, Richard Newton, like Grace, reveals depths that would surprise anyone who knows him only as the gentleman-sportsman who leads the hunt and paints with precision. Those who know a different Richard include the author of a hunt memoir who claims Richard’s violent temper was revealed to her one day when he gave a sound thrashing to a farmer who had strung a wire across his field. She also repeated a tale of his legendary courage after he and his horse fell into an abandoned well. Rescued only after he and the horse had spent three days and nights at the bottom of the well, he is said to have appeared at a dance that very night, offering no comment on what he termed a trifling accident. Richard’s prowess on horseback, his artistic talent, and the dazzling impression he makes in his scarlet hunting attire must have been irresistible to Grace, who also surely appreciates that they share artistic sensibilities and depths of character that have little to do with their obvious social graces.

In January 1905 a headline in the Kansas City Star announces the marriage of Mrs. Grace Clarke Bates to the Reverend Dr. Heber Newton’s son Richard with the headline: “An Artist Her Second Choice.” It hardly seems the kindest slant on the marriage, which takes place at 22 East 35th Street with Reverend Heber Newton officiating before the couple’s immediate relatives. The Star seizes the opportunity to dredge up the whole sad saga of Grace’s first marriage, which makes better copy than what would prove to be the happiest of unions for the next 10 years.

Subsequent editions of the Social Register list Mr. and Mrs. Richard Newton Jr. as residing with her parents in New York, though it is “Box Farm,” the Newtons’ shingled house in Water Mill on the corner opposite the Suffolk Hunt Club’s original headquarters which surely inspired this blissful reminiscence written by Grace:

“After this run, which was one of the most beautiful I ever saw, Dick riding ‘Tornado,’ I came back here, lit the lamps, got tea ready, and then when Dick rode in he saw the light shining from our own little house; he blew a ‘salute’ on his hunting horn and, in his pink coat, came home to tea. It is a memory long--no ever--to be cherished.”

Grace never stops writing poetry but she is also he author of the charming “A Hunting Alphabet,” which will appear with illustrations by her husband.

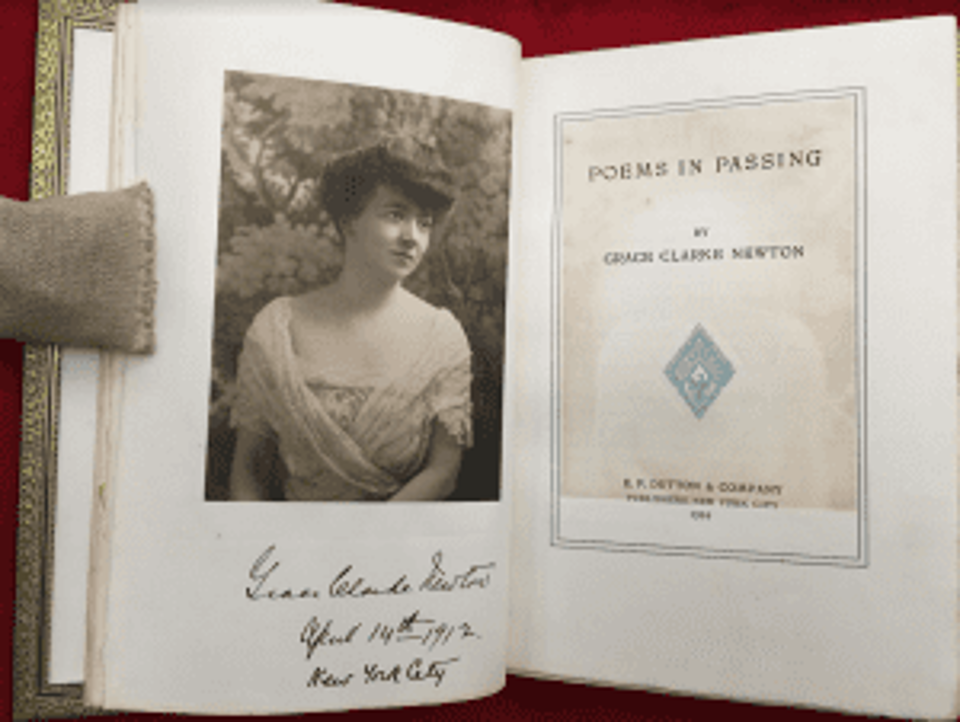

Then, in October 1915 the Newtons’ seemingly magical married life comes to an end when Grace, still a young woman, dies after what the local press identifies as “a lingering illness.” Her husband is devastated, and for her parents, who have lost the last of their four daughters to early deaths, it is a crushing blow. Immediately following Grace’s death, the grief-stricken Richard Newton edits and arranges for limited publication of some of his wife’s poetry in a collection that he illustrates, The result is a volume called Poems in Passing, which includes this particularly poignant poem:

“Canter far and free, Gallop fast and fleet. ‘Neath the dreamland tree We shall meet, my Sweet!”

In another memorial to Grace, Richard joins with his mother-in-law, Fanny Clarke, to make a sizable donation in Grace’s name to Southampton Hospital, earmarked for an addition to the X-ray department in the three-year-old building.

Grace’s story ends there but you may be interested to know what happened afterward to those whose life she touched.

Thanks to an idea hatched by Grace’s romantically impulsive first husband, Harry Wakefield Bates, brokers’ offices throughout the nation are able to have complete ticker-tape service, an innovation that accounts for the huge fortune he left at his death.

“Stage beauty” Elsie Ferguson, the obvious object of Thomas Clarke Sr’s affection years earlier at Stanford White’s luncheon, marries the Clarke’s only remaining offspring, Thomas Clarke Jr., in 1916--not the first time in this Gilded Age series that a father’s mistress has moved on to his son.

Richard Newton, made a widower in 1916 at Grace’s death, remarries twice. His 1918 marriage to Mildred Gautier Rice is dissolved in 1922, and 10 years later he marries the much younger Blanche Helier, who survives him by 24 years. When she dies in 1993, she wills Box Farm to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which finds a suitable purchaser in 1995. When the new owners move in, they discover leather-bound copies of Grace Clarke’s A Small Girl’s Stories and Poems in Passing.

Before his death in 1931, Thomas Clarke Sr. transforms his New York residence into an art gallery, and today 22 East 35th Street is the home of the Collectors Club, a private society whose members are avid stamp collectors.

.png)